Growing up, the war in Vietnam was a big deal to me and most young men of my generation. Some older guys had already been drafted, including one of my cousins, as well as the Greatest Boxer of all time. As I made my way through High School the prospect of being conscripted was very real.

Fortunately for me my Birthday was just late enough to miss the draft lottery so I didn’t have to decide whether to go or not to go.

Then the war ended and the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973, but fighting continued. The 50th anniversary of Saigon’s fall is coming up next year and it brings to mind memories of turbulent times both here at home, and over there in Vietnam. It also reminds me of someone I met years ago, after the war.

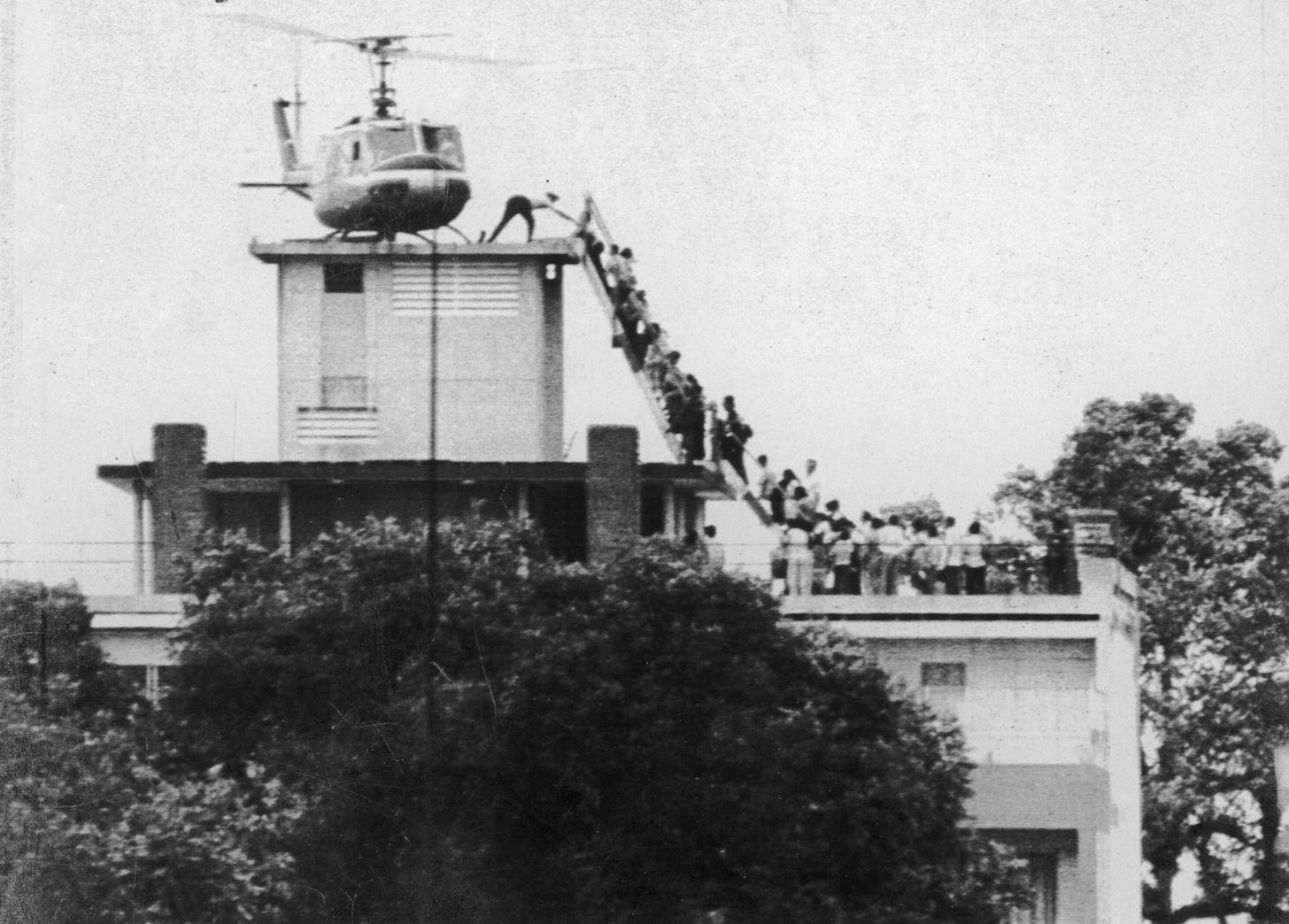

The Fall Of Saigon

In the early 1980’s I went to work for a mid-size company in Northern California as a Production Manager. The shop consisted of between six and ten people depending on the time of year. Machine operators, loading dock workers, shipping clerks, ordinary people doing ordinary work. The eighties were a great time in California, the economy was booming, Silicon Valley was exploding, and the internet was about to become reality. Possibilities seemed endless, and California was not the hopeless basket case it is today. Ronald Reagan, the once Governor was now President and it really did feel a bit like “MORNING IN AMERICA”.

Like most workplaces of that time ours was truly diverse, staffed by people from all over and of all backgrounds. One man working there stood out apart from the others. He was the forklift operator, I’ll call him Bao, and he’s perhaps one of the most interesting people I’ve ever known. Bao was from Vietnam and some things that differentiated him from the others were his smarts, innate business sense, and a persona of resilience. And while his English was perhaps not as good as the others he was still able to communicate with everyone, though it wasn’t always pretty.

There’s A Bomb

One day while I was away from the office a bomb threat was called into the company. Our Receptionist, (not someone for whom English was a second language, but she’s a story for another day), misunderstood the caller and thought he asked to speak with Bao, so she called him to the front to take his call. As he stood there, phone pressed to his face, he kept repeating over and over again “this is Bao” - “this is Bao”. Finally one of the Salesmen who was overhearing took over the phone. Can I speak with Bao was really: “there’s a bomb in the building”.

As it turned out there was no bomb, the call was a hoax, and since there was never any real danger, the whole incident quickly became a running joke around the office. We all had some laughs, even Bao.

Bao had been a helicopter pilot in the South Vietnamese Air Force during the war. On the day Saigon was overrun he, like many others had a quick decision to make, stay and be captured, perhaps killed, or get out right away. Bugging out was his only real choice.

Excerpt From Newsweek Online:

“The Day of the Copters

Eleven marines crouched on the flat roof of the U.S. Embassy, nervously fingering their M-16 rifles. From time to time, shots rang out from below, where thousands of Vietnamese milled about angrily in the embassy courtyard. Other Vietnamese were already rampaging through the lower floors of the six-story building, trying to make their way up tear-gas-filled stairwells. Suddenly, the whine of a helicopter could be heard in the distance and the Marines fired a red-smoke grenade to mark their position. As the U.S. CH-46 Sea Knight touched down on the roof, the Marines piled into the chopper.

At long last, America's military involvement in Vietnam was over. While Operation Frequent Wind, the final American evacuation, was a logistical success, four U.S. Marines were killed on that final day—bringing to 56,559 the number of Americans who died in Vietnam. It was the biggest helicopter lift of its kind in history—an 18-hour operation that carried 1,373 Americans and 5,595 Vietnamese to safety.

Yet in sheer numbers, the feat was overshadowed by the incredible impromptu flight of perhaps another 65,000 South Vietnamese. In fishing boats and barges, homemade rafts and sampans, they sailed by the thousands out to sea, hoping to make it to the 40 U.S. warships beckoning on the horizon. Many were taken aboard the American vessels, while others joined a convoy of 27 South Vietnamese Navy ships that limped slowly—without adequate food or water—toward an uncertain welcome in the Philippine Islands. Hundreds of South Vietnamese also fled by military plane and helicopter, landing at airfields in Thailand or ditching their craft alongside American ships.”

Bao was one of those who ditched. He flew his chopper as far and as fast as he could out of harms way, over the ocean, eventually finding himself in the water. Unfortunately, having to leave so quickly had left no time to locate and gather his family, a wife and young child.

Plucked from the sea by the American Navy he became another refugee of the failed war and was brought to America. By the early 1980’s, when I met him, he was living in California, working the forklift, and trying to locate his family so he could bring them over.

In 1989 I left the company, but stayed in touch with some of the people there. A couple of years later the Northern office was closed and combined with the Southern California division. Before long, everyone moved on with their lives, and I eventually lost contact with the others, but before that happened I learned that Bao had reunited with his family and they joined him here in the early 1990’s.

When Losing Becomes A Habit

Thinking of post WWII America it’s hard to ignore the wars our country no longer fights to win. Vietnam may not have been the first, certainly it has not been the last, but it has to be the “poster child” of American war losses. American military involvement in Vietnam lasted about a decade, with nearly 57,000 soldiers killed in combat, many more terribly injured, both physically and mentally, families were destroyed, and many young men (including my cousin) returned home with serious drug addictions and mental illnesses, the societal costs have been enormous and multi-generational.

The 9-11 attacks, incurred a larger death toll than Pearl Harbor, generated two wars, Iraq and Afghanistan, neither of which were fought with victory as the goal. The wars just seem to get longer, more costly, and more pointless. Different decades, different locations, same result.

Eisenhower’s farewell address warning of January 17, 1961 seems more prophetic than ever: “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex”.

The Last Chopper

On a clear, sunny afternoon I walked into the warehouse at lunchtime, the quiet hour. At the edge of an open loading dock door stood Bao, gazing off somewhere over the horizon, in the distance a chopper could be heard approaching, getting audibly louder.

I approached Bao and asked him how he was doing. He turned to look at me, a slight smile appearing on his face as he asked me if I could hear the helicopter, I nodded in the affirmative. He said hearing that sound always reminded him of home, of Vietnam. I think I may have nodded again. I don’t recall much conversation after that, we both just stood there for a moment side by side looking, listening. Two men from entirely different backgrounds and from opposite sides of the world, that somehow ended up here at this same time.

Lunchtime ended, and the distant hum of a lone chopper faded away, replaced by the sounds of machines turning on, racks and carts moving around, and the usual banter that goes on in a warehouse. Bao and I walked off in different directions. Time to go back to work.

🌹🌻🌸💐💚💛💜❤️🌼😍🥰

An awesome read, thank you for crafting it and passing on your experiences and thoughts.

Much respect

Dominus